Recent years have seen a global shift towards illiberal forms of governance, where democratic institutions and liberal norms are progressively undermined. These regime transitions carry not only political implications but also deep economic and social consequences, as policy priorities shift and the distribution of state resources is reshaped.

Immigration is often a central force in these dynamics. In periods of heightened cross-border migration, host societies – especially those experiencing institutional fragility – may respond with heightened political tension. Cultural anxieties, fears over labour market competition, and concerns about the sustainability of welfare systems frequently come to the fore (Dustmann et al. 2019, Halla et al. 2017).

Research by Loungani and Razin (2001) and Razin and Wahba (2015) has shown how welfare-state dynamics affect the composition of migrants along skill lines. More recent political economy literature extends this work by exploring the role of regime type – liberal versus illiberal – in shaping migration flows (Hatton and Williamson 2002, Geddes 2015).

Liberal democracies tend to attract immigrants and retain native talent due to their civil liberties, personal security, and institutional predictability. In contrast, illiberal regimes often drive out citizens – particularly the skilled and educated – by curtailing freedoms and limiting economic prospects (Docquier et al. 2007).

De Haas et al. (2019) argue that democratisation initially spurs emigration as mobility restrictions are lifted and aspirations rise. But over time, democratic consolidation tends to reduce emigration as governance and development improve. Conversely, democratic backsliding triggers large-scale emigration – especially ‘brain drain’ – well before formal institutional changes occur (Boeri et al. 2012, Giuliano and Spilimbergo 2009).

Portes (2022) examines the impact of the Brexit-induced regime change on migration and trade. Long-term migration preferences, inferred from voting data, are studied by Peri et al. (2022). Transitions from liberal to illiberal democracies have profound effects on real economic indicators such as growth (Razin 2024).

In a recent paper (Razin 2025), I employ the Civil and Human Rights Integrity (CHRI) Index to capture the institutional quality and robustness of civil rights across countries. Within the EU, both emigration and immigration are shaped not only by domestic factors but also by the institutional and economic frameworks of integration.

Empirical strategy and data

I employ a difference-in-differences (DiD) framework to isolate the causal effects of regime change and migration on one another. The core variables include:

- The Civil and Human Rights Integrity (CHRI) Index, a proxy for institutional strength and rule of law.

- Immigration and emigration flows (as percentages of the labour force).

- EU accession and membership, a measure of economic integration.

The sample covers 2006-2023 and includes EU and OECD member states, as well as select non-EU advanced economies. Data sources include the OECD, the Fund for Peace, and national statistical agencies.

Key findings and interpretations

Immigration and the quality of legal governance

Figure 1 provides empirical support for the hypothesis that immigration may contribute to institutional weakening in host countries. We see that higher CHRI values – signifying weaker governance – are positively associated with increased immigration-to-labour-force ratios. This effect is particularly pronounced in EU countries. These findings suggest that rising immigration flows may exacerbate institutional fragility, especially in politically vulnerable democracies. While immigration brings economic and demographic benefits, it can also strain governance frameworks when institutions are already under pressure.

Figure 1 Legal governance and immigration, EU countries

Source: OECD, Fund for Peace

Notes: 2006-2023, sample of countries: Austria, Belgium, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey and United Kingdom. An increase in the CHRI measures of legal governance is indicative of a deterioration in the rule of law, with higher CHRI values corresponding to weaker institutional and legal enforcement.

Emigration in response to illiberal regime shifts

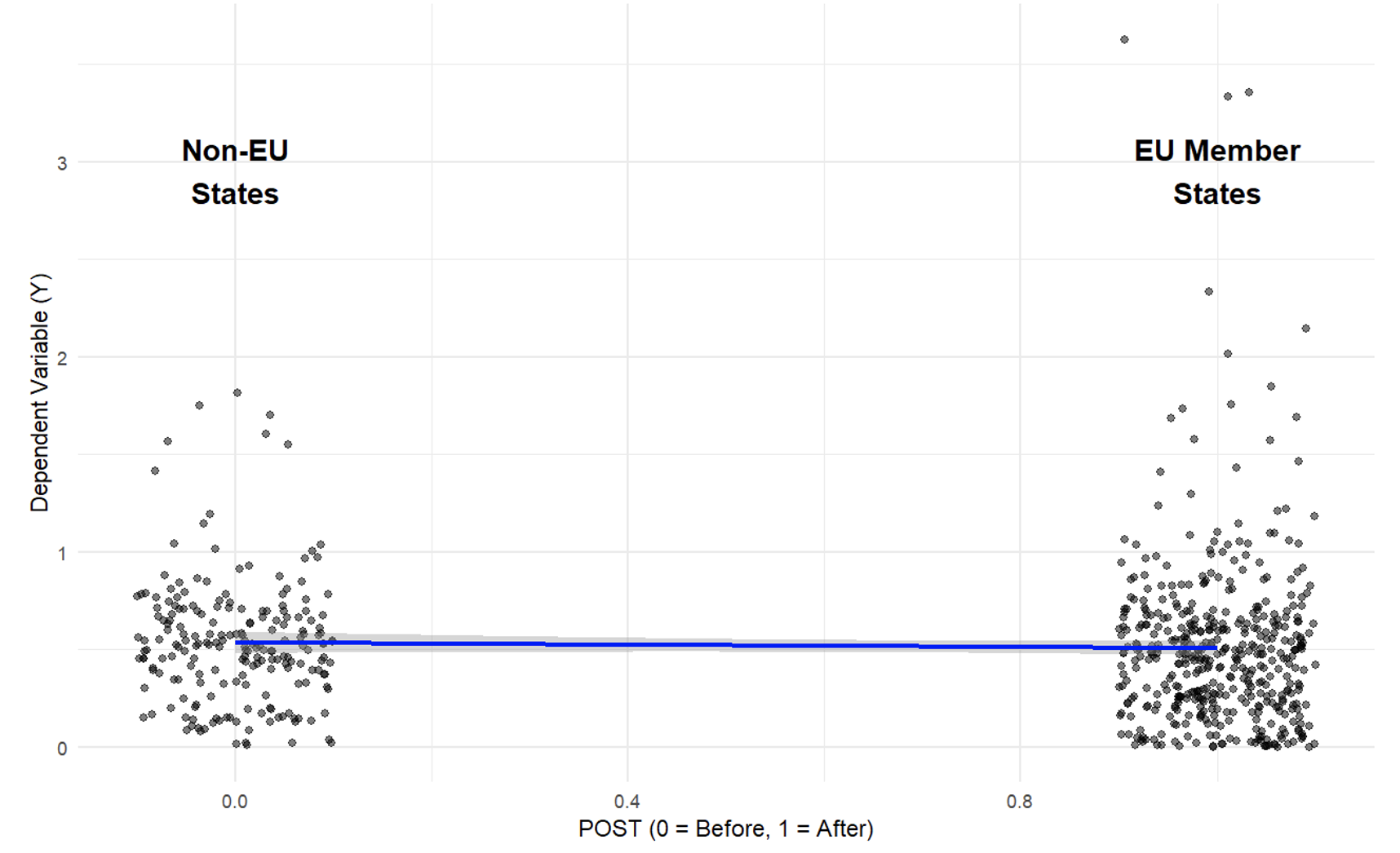

Panels A and B of Figure 2 explore the emigration response to regime transitions from liberal to illiberal political systems. Using the difference-in-differences method, we introduce a treatment dummy variable, POST1, which equals 1 in the year of the regime change and all subsequent years.

We observe a marked rise in emigration rates following such transitions, particularly among the educated workforce. This supports the view that political repression and uncertainty drive anticipatory emigration, undermining the capacity for future institutional recovery.

Figure 2 Emigration response to regime transitions

A) Emigration and liberal-illiberal regime transition, OECD countries

B) Average emigration-to-labour ratio before and after transition from liberal to illiberal regime

Source: OECD.

Notes: 1995-2023 (when possible), sample of countries: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, Korea, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Mexico, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, United Kingdom, and United States. POST1 is a dummy variable that equals 1 for all years following (and including) the year in which a country experiences a regime change from a liberal to an illiberal political system. It takes the value of 1 for countries that undergo such a transition, starting from the year of the change and continuing in all subsequent years. For countries that do not experience a liberal-to-illiberal transition during the sample period, POST1 remains 0 throughout. In the difference-in-differences (DiD) regression, the ‘treatment’ variable is a dummy indicating the year of the regime change.

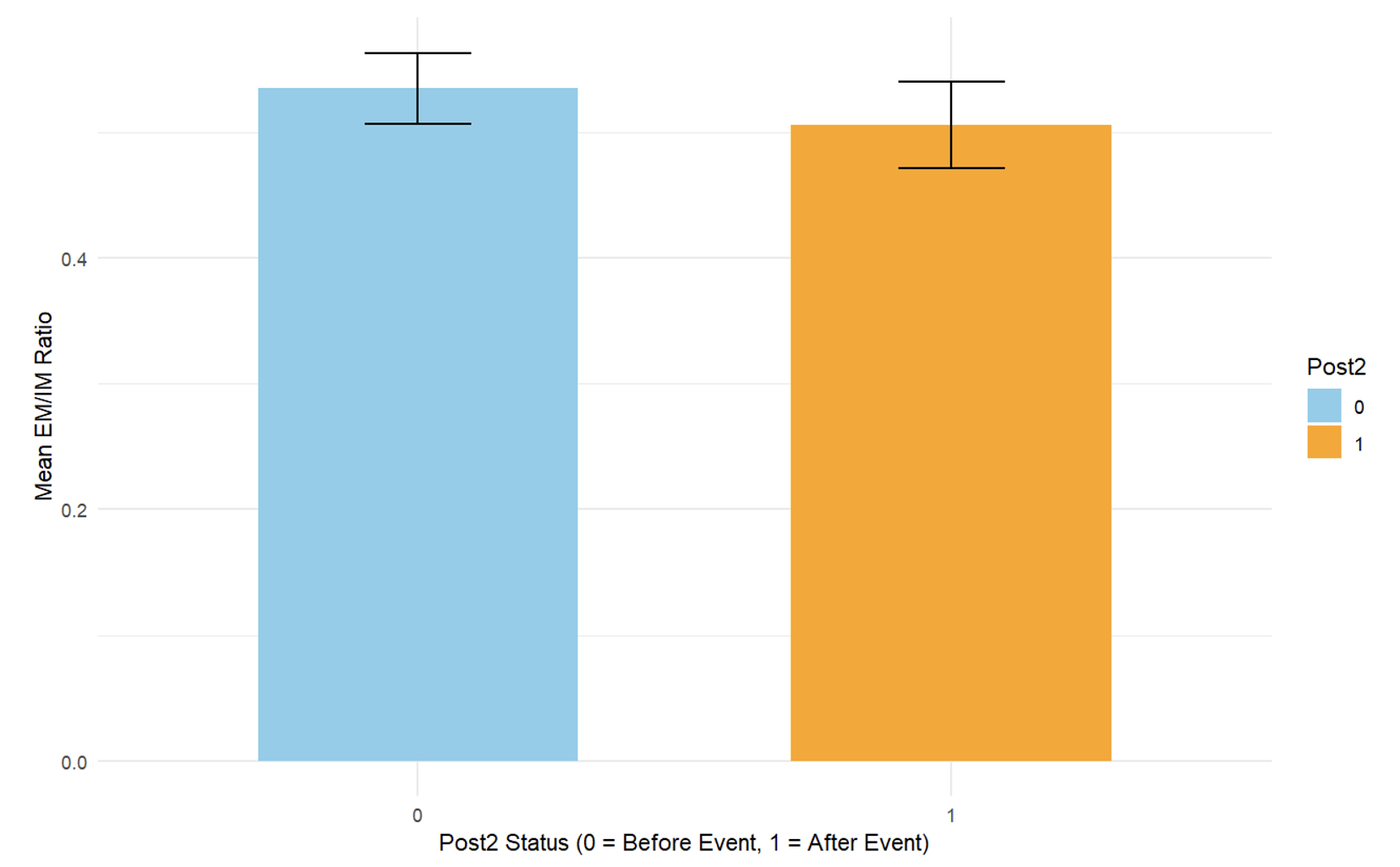

Emigration and access to the EU

International economic integration – particularly through EU accession – facilitates emigration from weak democratic countries. Countries that became EU members exhibit increased emigration from the year of accession onward. The timing of EU accession is captured by the variable POST2, a dummy that takes a value of 1 starting in the year a country joins the EU and remains 1 in all subsequent years. For countries that did not join the EU during the sample period, POST2 remains 0 throughout. This variable identifies the potential impact of EU membership on migration and related economic or institutional outcomes.

Panels A and B of Figure 3 show that accession to the EU has a positive effect on emigration flows: countries that became EU members exhibit increased emigration from the year of accession onward. The timing of EU accession is captured by the variable POST2, a dummy that takes a value of 1 starting in the year a country joins the EU and remains 1 in all subsequent years. For countries that did not join the EU during the sample period, POST2 remains 0 throughout. This variable identifies the potential impact of EU membership on migration and related economic or institutional outcomes.

Figure 3 Emigration flows and accession to the EU

A) Emigration and access to the EU, OECD countries

B) Mean emigration-to-immigration ratio by EU accession status

Source: OECD.

Notes: 1995-2023 (when possible), sample of countries: Austria, Belgium, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey and United Kingdom. POST2 is a dummy variable that takes the value 1 starting from the year a country joins the European Union (EU) and for all subsequent years. It captures the post-accession period for EU member states. For countries that never joined the EU during the sample period, POST2 remains 0 throughout. This variable is used to identify the potential effects of EU membership on relevant economic or institutional outcomes. In the difference-in-differences (DiD) regression, the ‘treatment’ variable is a dummy indicating the year of the regime change.

Domestic legal governance and global emigration pressures

Figure 4 demonstrates a significant inverse relationship between emigration from other countries and a country’s CHRI score. That is, increases in emigration abroad correlate with improvements in domestic legal governance.

One interpretation is that global emigration surges – possibly triggered by economic or political shocks – prompt receiving countries to bolster institutional quality in order to manage these pressures effectively.

Figure 4 Governance and external emigration pressures, EU countries

Notes: Sample countries: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, Korea, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Mexico, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, United Kingdom, United States.

Higher CHRI scores indicate weaker rule of law.

Conclusion and policy implications

This column has explored the dynamic interrelationship between migration flows and political regime change, particularly the transition from liberal democratic systems to illiberal or hybrid regimes. The empirical findings – grounded in cross-country panel regressions and difference-in-differences analysis – highlight a dual causal mechanism. First, deteriorating democratic institutions tend to trigger emigration surges, as individuals seek stability, opportunity, and security elsewhere. Second, rising immigration – particularly in advanced economies – can place pressure on institutional capacity, potentially weakening the rule of law and contributing to illiberal political drift.

This column underscores the reciprocal relationship between migration and regime change. Key implications include the following:

- For liberal democracies: Institutional robustness must be safeguarded in the face of large immigration inflows. Policy frameworks should be designed to integrate migrants without fuelling political backlash or institutional erosion.

- For countries facing democratic decline: Emigration – especially of skilled individuals – can further destabilise institutions. Policymakers must understand and mitigate these outflows to maintain reform capacity.

- For the EU and integration processes: EU accession and membership can serve as stabilising forces, reducing the adverse effects of political transitions on migration by anchoring countries in liberal-democratic norms.

References

Boeri, T, H Brücker, F Docquier and H Rapoport (2012), Brain drain and brain gain: The global competition to attract high-skilled migrants, Oxford University Press.

de Haas, H, M Czaika, M-L Flahaux, E Mahendra, K Natter, S Vezzoli and M Villares-Varela (2019), “International Migration: Trends, Determinants, and Policy Effects”, International Migration Institute.

Docquier, F, O Lohest and A Marfouk (2007), “Brain drain in developing countries”, The World Bank Economic Review 21(2): 193-218.

Dustmann, C, U Schönberg and J Stuhler (2019), “Labor Supply Shocks, Native Wages, and the Adjustment of Local Employment”, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 435–497.

Geddes, A (2015), “Governing migration from a distance: interactions between climate, migration, and security in the South Mediterranean”, European Security, 473-490.

Giuliano, P and A Spilimbergo (2009), “Growing Up in a Recession: Beliefs and the Macroeconomy”, NBER Working Paper 15321.

Halla, M, A F Wagner and J Zweimüller (2017), “Immigration and Voting for the Far Right”, Journal of the European Economic Association, 1341–1385.

Hatton, T J and J G Williamson (2002), “What Fundamentals Drive World Migration?”, NBER Working Paper 9159.

Loungani, P and A Razin (2001), “How Beneficial Is Foreign Direct Investment for Developing Countries?”, Finance and Development.

Peri, G, R Turati and S Moriconi (2022), “Long-term political consequences of Immigration: Voting preferences of immigrations' children in European countries”, VoxEU.org, 13 November.

Portes, J (2022), “Trade, migration and Brexit”, VoxEU.org, 8 September.

Razin, A (2024), The Transition to Illiberal Democracy: Economic Drivers and Consequences, CEPR Press.

Razin, A (2025), “Migration and Regime Change: Outflows Follow Democratic Decline, Inflows Fuel Illiberal Drift”, CEPR Discussion Paper No. 20200.

Razin, A and J Wahba (2015), “Welfare Magnet Hypothesis, Fiscal Burden, and Immigration Skill Selectivity”, The Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 369-402.