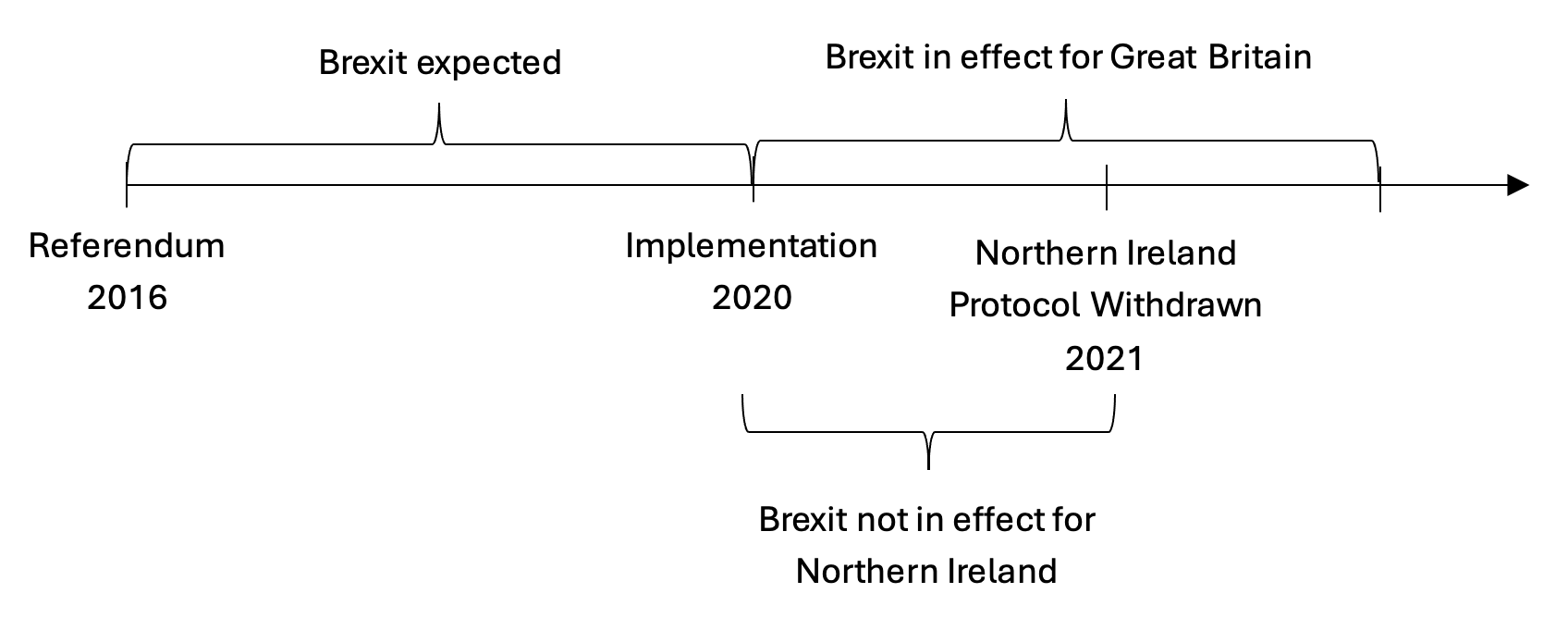

The Brexit process created a distinctive institutional context within the UK. Although the entire country voted in the 2016 referendum on EU membership, the subsequent implementation of Brexit produced markedly different experiences for Great Britain and Northern Ireland. In January 2020, Brexit formally took effect, leading to an immediate and comprehensive economic separation between Great Britain – comprising England, Scotland, and Wales – and the EU. New trade, economic, and regulatory barriers emerged immediately. Northern Ireland, however, followed a different trajectory. Under the terms of the Northern Ireland Protocol, it effectively remained within the EU’s Single Market for goods, avoiding a hard border with the Republic of Ireland and enabling businesses to continue trading freely with the European market until early 2021.

This divergence created a unique natural experiment: two regions under the same national governance, yet subject to different economic regimes due to policy design in Figure 1. To exploit this setting, in Do et al. (2024) we employ a novel identification strategy based on firms' geographic proximity to the Irish border. Firms located closer to the border – particularly within Northern Ireland – were less exposed to the full economic consequences of Brexit, while those situated further away – primarily in Great Britain – encountered more significant trade disruptions. Importantly, by restricting the sample to firms that had remained in their pre-referendum locations, this approach minimises concerns regarding endogenous relocation in response to Brexit uncertainty. Distance to the border thus serves as an exogenous proxy for Brexit exposure, enabling a cleaner estimation of the differential economic impacts induced by the UK's withdrawal from the EU. This contrast between Great Britain and Northern Ireland allows us to hinge the identification strategy based on the Irish border.

Figure 1 The anatomy of Brexit timing: Northern Ireland vs. Great Britain

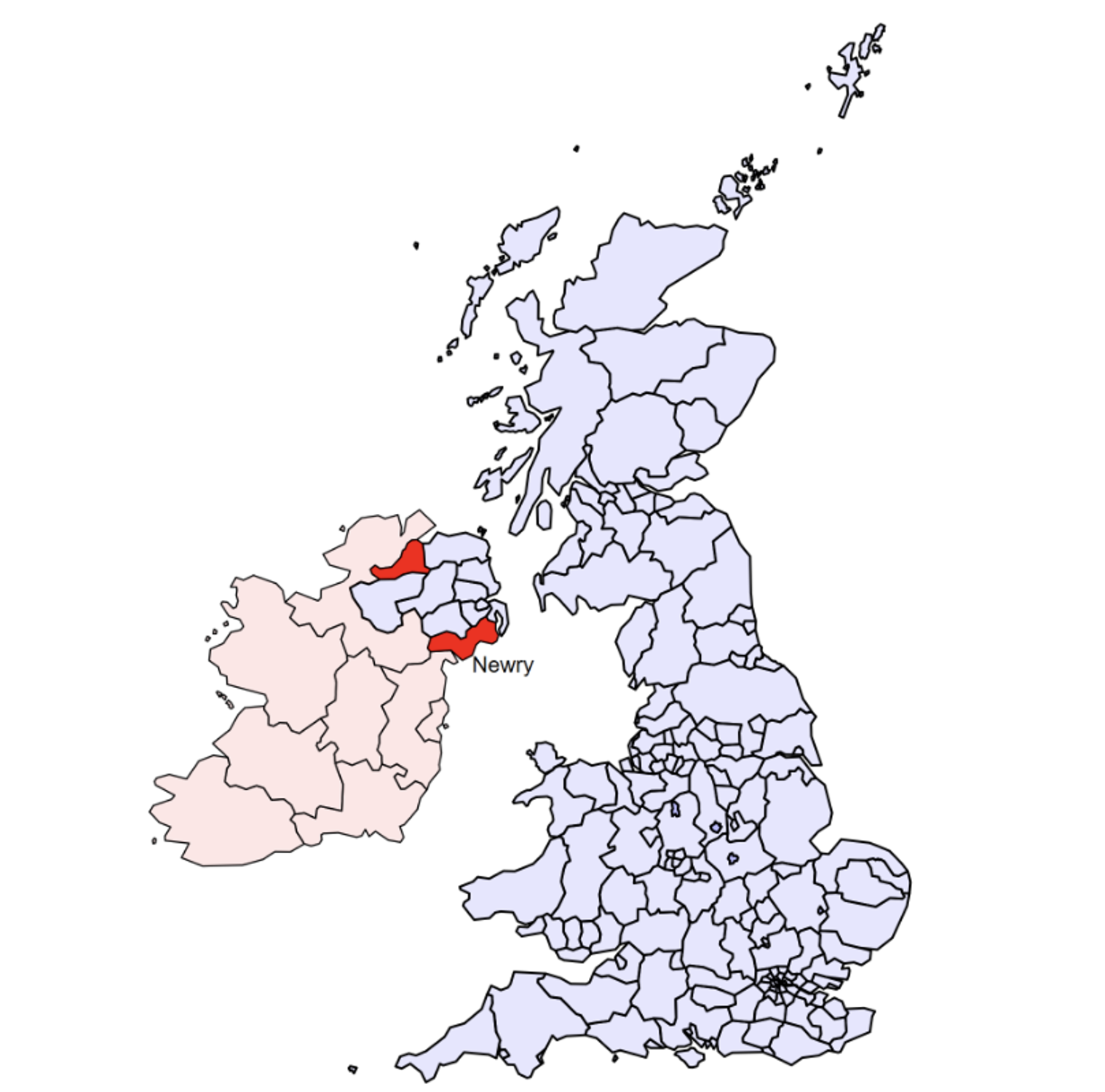

The distance to Newry – a border city near the Republic of Ireland along the Belfast-Dublin route that offered firms easier EU access after Brexit under the Northern Ireland Protocol – is central to our identification strategy, as shown in Figure 2. Our study uses distance to Newry as a plausibly exogenous proxy for Brexit exposure to isolate its causal effects on economic outcomes. Results are robust to using alternative border points, such as the Derry port.

Figure 2 Map of the United Kingdom and distance to Newry port

Notes: The ports of Newry and Derry are in red while the rest of the United Kingdom is in light blue. Republic of Ireland is in light red.

The real Brexit effects on labour demand

We use data from the UK Longitudinal Small Business Survey (LSBS) covering 2015–2022, which provides detailed firm-level information on employment, location, and business characteristics. Firms’ locations are identified using Local Enterprise Partnerships (LEPs) and matched to Local Authority Districts (LADs) through postcode information. Our study examines the real effects of Brexit implementation on labour demand among UK firms, using the distance to Newry as a proxy for Brexit exposure. Firms further from the Irish border – those more exposed to Brexit-related trade barriers – reduced their workforce by up to 15.7% relative to firms located closer to the border. Our results are robust to a range of checks, including using alternative border points (such as Derry port), placebo tests with randomised distances, and Brexit timing, excluding the Brexit referendum period, accounting for COVID-19 impacts, and incorporating additional firm-level controls. In Figure 3, before the implementation of Brexit, both groups had similar employment trends, but a clear divergence appears after 2020, with high-exposure firms reducing their workforce significantly.

Figure 3 Employment of high- vs. low-exposure firms

Notes: Figure 3 shows the average (log) number of employees for firms by Brexit exposure. Low-exposure firms (N = 21,395) are within the median distance to Northern Ireland’s border; high-exposure firms are farther. The figure includes 95% confidence bands and marks three key events: the referendum (2016), Brexit implementation (2020), and Northern Ireland Protocol withdrawal (2021).

Our results complement the large and growing literature on Brexit. Bloom et al. (2019) show that around 10% of 42,000 surveyed UK businesses identified labour availability as the main source of Brexit-related uncertainty, underscoring its impact on workforce dynamics. The findings also align with evidence on post-Brexit labour reductions (Fuller 2021, Sampson 2017) and the decreased accessibility of the British labour market to foreign workers (Born et al. 2019).

Heterogeneous effects of Brexit on thelabour demand

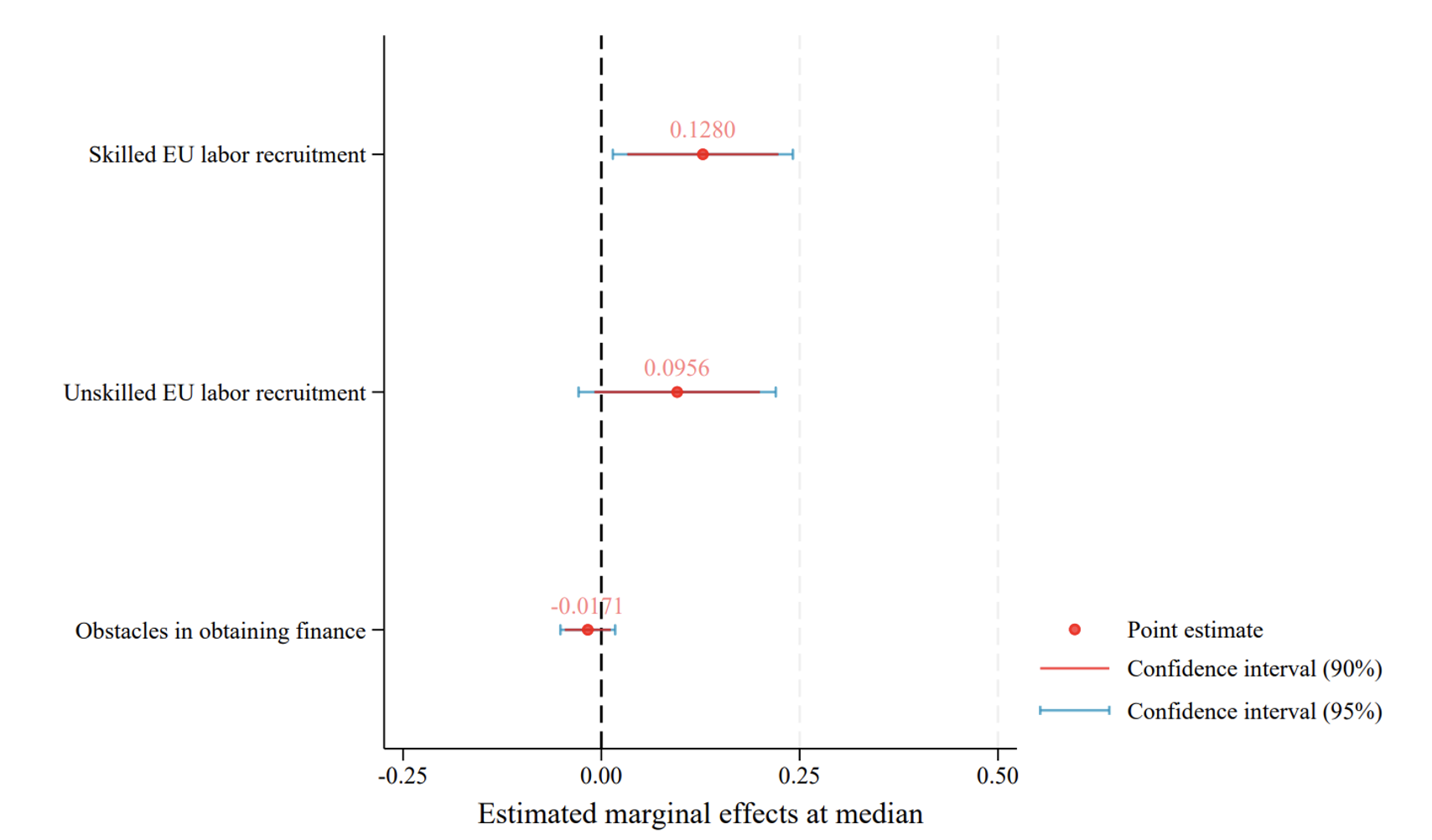

Our study also highlights important industry heterogeneity in the impact of Brexit on firms’ ability to recruit skilled EU workers. Figure 4 shows that firms more exposed to Brexit, measured by greater distance from the Irish border, are more likely to report difficulties hiring skilled EU workers after 2020. This relationship holds even after adding firm-level controls. The results suggest that industries vary in their exposure to Brexit-induced recruitment challenges, with some sectors more affected than others. Firms in industries that previously relied more on EU labour experienced sharper increases in hiring difficulties, while others remained relatively less impacted.

Importantly, the robustness of these findings – even when excluding firms that moved locations – strengthens the causal interpretation. Our approach isolates the industry-specific effects of Brexit on labour demand, highlighting that recruitment difficulties are not evenly distributed across the economy. These results emphasise the need to account for industry heterogeneity when assessing the real effects of Brexit on firms' ability to source EU skilled labour. Sectors such as construction and professional services experienced larger negative impacts, reflecting their greater exposure to trade barriers and reliance on EU labour. In contrast, sectors like retail and local services saw smaller declines, suggesting lower sensitivity to Brexit-related disruptions. The average effect across industries is negative, with considerable variation in magnitude. These results highlight that while Brexit broadly reduced labour demand, the intensity differed depending on the industry’s structure, emphasizing the importance of accounting for industry heterogeneity.

Figure 4 Coefficient plots for difficulty in recruiting/retaining (un)skilled EU labour

Notes: Figure 4 shows the marginal effects (at the median) from a Probit regression estimating the impact of Brexit exposure on firms' difficulties recruiting skilled and unskilled EU workers. The model includes distance to Newry, a Brexit dummy, and industry fixed effects. Results are included with and without additional controls (firm age, residential office, female ownership, legal status, labour supply, and excluding firms that switched locations).

What alleviates the Brexit effects?

Two key mechanisms help alleviate the real effects of Brexit on firms’ labour demand: the R&D substitution effect and pre-existing trade exposure. First, firms facing higher Brexit exposure increasingly invested in research and development (R&D) activities. The results show that a 1% increase in distance from the Irish border is associated with an increase of approximately one category in R&D spending. This shift suggests that firms substituted away from labour-intensive operations toward more technology-driven processes, using innovation as a strategy to adapt to trade disruptions. Although labour demand declined, increased R&D activity partially offset the employment losses, demonstrating that adverse shocks can stimulate technological responses. This result complements the existing debates on automation and employment in the context of trade barriers (Zeira and Nakamura, 2018).

Second, trade exposure significantly mitigated the negative employment impacts of Brexit. Firms with pre-existing trade links, whether with the EU or globally, experienced smaller reductions in labour demand compared to firms without trade exposure. Estimates indicate that, although exposed firms generally reduced employment by up to 15.7%, those with prior trade experience saw notably smaller contractions. The ability to access diversified markets and leverage established international networks helped firms better adjust to the post-Brexit environment. Although the level of trade between UK firms and the EU is declining (Freeman et al. 2025), the findings suggest that having prior trade exposure helped British firms mitigate labour reductions.

Overall, the evidence highlights that adaptability through innovation and global engagement was crucial in mitigating the negative real effects of Brexit. Firm-specific characteristics, such as investment in R&D and international experience, played an essential role in absorbing and responding to large economic shocks.

References

Bloom, N, P Bunn, S Chen, P Mizen, P Smietanka and G Thwaites (2019), “The impact of Brexit on UK firms”, NBER Working Paper No. w26218.

Born, B, G J Müller, M Schularick and P Sedláček (2019), “The costs of economic nationalism: Evidence from the Brexit experiment”, The Economic Journal 129(623): 2722-2744.

Do, H, K Duong, T Huynh and N T Vu (2024), “The Real Effects of Brexit on Labor Demand: Evidence from Firm-level Data”, CGR Working Paper No 117. Queen Mary University of London, School of Business and Management, Centre for Globalisation Research.

Freeman, R, M Garofalo, E Longoni, K Manova, R Mari, T Prayer and T Sampson (2025), “Deep integration and trade: UK firms in the wake of Brexit", VoxEU.org. 7 April.

Fuller, C (2021), “Brexit and the discursive construction of the corporation”, Journal of Economic Geography 21(2): 317-338.

Sampson, T (2017), “Brexit: the economics of international disintegration”, Journal of Economic Perspectives 31(4): 163-184.

Zeira, J and H Nakamura (2018), “Automation and Unemployment: Help is on the Way”, VoxEU.org, 11 December.