Have you ever entered an outlet that looks like more than merely a place of business? The owner and/or some of the employees are local public figures. Regulars are greeted by their first names. Services (such as keeping keys) are provided to whomever needs them. The place is bursting with life, and each visit delivers its lot of entertainment. Serving as a social hub for weak ties and sidewalk acquaintances, it provides a short retreat from the stress of everyday life. If you know such an outlet, you are lucky to know a ‘third place’ (Oldenburg 1999), a spiritual tonic beyond home and work.

Third places can take many forms: cafés, bars, food stores, convenience stores, barbers, hairdressers, etc. They are often at the heart of a neighbourhood, literally and figuratively. Indeed, knowing about them is a mark of belonging to the local community. Sociologists have highlighted their importance in building ‘thin’ trust between locals (Oldenburg 1999 and Jacobs 1961 pre-eminently). Urban planners have stressed their vital role for a better city life (e.g. Gehl 2013, Moreno 2024). But until recently, economists and political scientists have been less aware of their social and political significance.

Fetzer et al. (2024) used survey data to measure the impact of shop vacancies in the UK on the intention to vote for the UK Independence Party (UKIP) – the main populist party in the country until its rebirth as the Brexit Party and then Reform UK – but attribute their findings to local economic decline rather than the social role played by these outlets. Also using survey data, Bolet (2021) examines how the closure of community pubs increases reported willingness to cast a ballot for UKIP. Davoine et al. (2020 in French, summarised in English in Algan et al. 2020) highlight a correlation between the disappearance of services and stores in a community and protest events by the ‘gilets jaunes’ in France.

In a recent paper (Wolton et al. 2024), we complement these works in multiple ways. We look at local election results over the period 2011–2019 in the UK, using geolocalised data on outlets at the postcode level (the smallest administrative unit) obtained from Point X. Our rich dataset contains more than 13.5 million outlet-year observations, which we aggregate at the ward level, the smallest unit for which electoral data are available. We use independent consumer outlets as a proxy for third places. Independent consumer outlets consist of eating and drinking establishments, legal and financial services, personal services, property services, and any retail shops not characterised as a ‘brand’ by Point X. We track how the evolution of these outlets in a ward over time affects support for UKIP. We further study how the effect of third places compares to the impact of branded consumer outlets and other outlets (B2B services, sport and entertainment, education and health services). We find that the presence of independent consumer outlets reduces the vote share for UKIP in local elections even after controlling for multiple economic and socio-demographic factors. Branded consumer outlets and other outlets have no effect on support for the populist party.

Figure 1 High street changes and UKIP support in local elections

Note: Figure plots the coefficients from a linear regression that includes controls for economic factors (e.g. house prices), socio-demographic factors (e.g. ethnic composition), ward fixed effects, and local authority year fixed effects (as each ward is nested in one local authority).

Is this enough to recover the political consequences of third places? Probably not. Despite our multiple controls, part of the effect we obtain may be due to local areas thriving or suffering economically. Yet, a series of additional tests suggest that economic circumstances are unlikely to fully explain the impact of independent consumer outlets on populist vote share. The data we have allow us to separate between old outlets (present in a local area for more than a year) and new outlets (less than a year old). If the economy is the key factor, old and new independent consumer outlets should have the same electoral consequences. Our analysis suggests that only the presence of old independent consumer outlets reduces the vote share for UKIP.

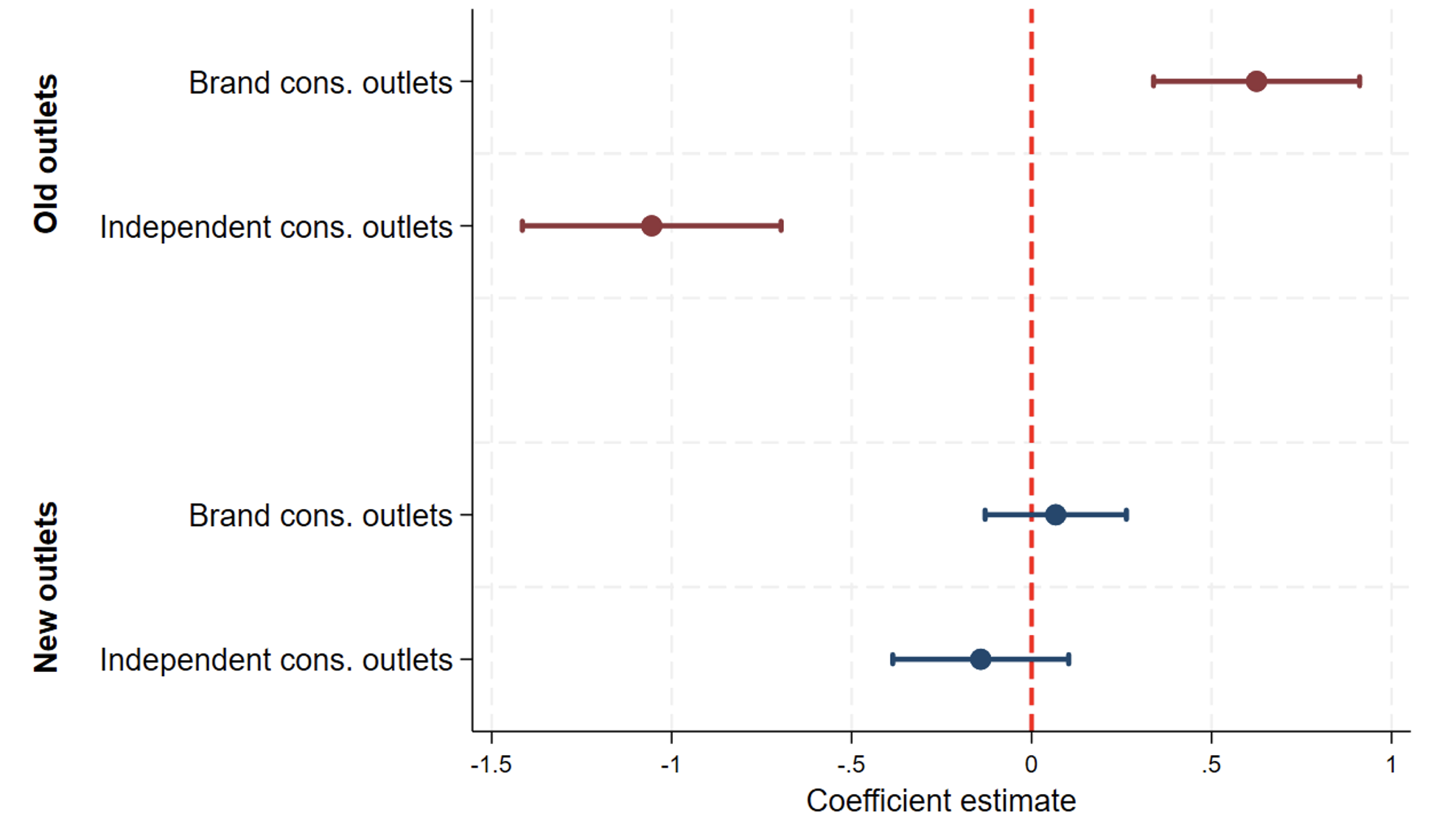

Figure 2 Old and new outlets and the support for UKIP

Note: Figure plots the coefficients from a linear regression that includes controls for other outlets, economic factors (e.g. house prices), socio-demographic factors (e.g. ethnic composition), ward fixed effects, and local authority year fixed effects (as each ward is nested in one local authority).

We go even further. When building our measure of independent consumer outlets, we grouped together very different types of commercial places: personal services with property services, convenience stores with garages. Arguably, some of those business categories serve more of a social function than others, especially drinking and eating places, personal services (e.g. barbers), household goods stores (e.g. bookstores), and food stores. We show that those social outlets are the ones driving our main results: their presence negatively correlates with populist success.

Figure 3 Independent consumer outlet types and support for UKIP

Note: Figure plots the coefficients from separate linear regressions, each including controls for brand outlets of the same category, other outlets (including other consumer outlets), economic factors (e.g. house prices), socio-demographic factors (e.g. ethnic composition), ward fixed effects, and local authority year fixed effects (as each ward is nested in one local authority).

Beyond the effect of immigration and globalisation (Docquier et al. 2024, Ottaviano et al. 2021), beyond the effect of terrorism (Sabet et al. 2023), and beyond the effect of economic shocks (Sonno et al. 2022) and austerity (Klein et al. 2022), our work highlights a new channel through which populists gain traction. The mechanisms we uncover are distinct from previous works. Indeed, this is not a ‘left-behind’ phenomenon. Urban, middle-class, young areas are the most reactive to change in their high streets, as we show in the paper. As such, our findings highlight how populism spreads through all strata of society.

What can be done about it? Governments and local authorities often put in place policies to revitalise the high street. Yet, to build a real local community – or at least, a sense of communality – it is not enough to just fill the space. Pop-up shops by their transient nature will fail to revive an area. Branded consumer outlets may hurt rather than help. It is important to identify outlets that will serve as focal points and local figures who will invest socially in their local area. ‘One size fits all’ policies will not work. In this sense, the UK government’s new policy giving more power to local councils to auction off leases for commercial properties that have been empty for long periods is a welcome step (HM Government 2024). Moving forward, our work provides an argument for subsidising third places given the positive externality they generate within their neighbourhoods.

References

Algan, Y, C Margouyres and C Senik (2020), “Small retail businesses: decline or mutation?”, Les Notes du Conseil d'Analyse Economique no. 55, January.

Bolet, D (2021), “Drinking alone: local socio-cultural degradation and radical right support – the case of British pub closures”, Comparative Political Studies 54(9): 1653–92.

Davoine, E, E Fize and C Malgouyres (2020), “Les déterminants locaux du mécontentement: analyse statistique au niveau communal”, Conseil d'Analyse Economique, 039-2020, January.

Docquier, F, S Iandolo, H Rapoport, R Turati and G Vannoorenberghe (2024), “Populism and the skill content of globalization”, VoxEU.org, 12 March.

Fetzer, T, J Edenhofer and P Garg (2024), “Local decline and populism”, VoxEU.org, 15 September.

Gabriel, R D, M Klein and A S Pessoa (2023), “The political disruptions of fiscal austerity”, VoxEU.org, 15 December.

Gehl, J (2013), Cities for people, Washington, DC: Island press.

HM Government (2024), “Huge boost for high streets as councils get new powers”, press release, 3 December.

Jacobs, J (1961), The Death and Life of Great American Cities, New York: Random House.

Moreno, C (2024), The 15-Minute city: A solution to saving our time and our planet, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons.

Oldenburg, R (1999), The great good place: Cafes, coffee shops, bookstores, bars, hair salons, and other hangouts at the heart of a community, Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press.

Ottaviano, G, P Stanig and I Colantone (2021), “The globalisation backlash”, VoxEU.org, 1 November.

Sabet, N, M Liebald and G Friebel (2023), “Terrorism and voting: The rise of right-wing populism in Germany”, VoxEU.org, 31 May.

Sonno T, H Herrera, M Morelli and L Guiso (2022), “Financial crises as drivers of populism: A new channel”, VoxEU.org, 7 July.

Wolton, S, S Gasimova, R Paccioretti, G Palladino and P Scribante (2025), “The Structural Transformation of the Public Space: High-Street Changes and Populism”, CEPR Discussion Paper no. 19932.